- Home

- Anne Boileau

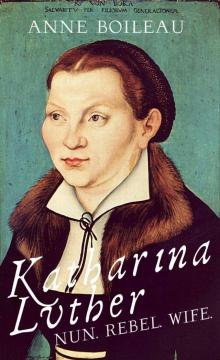

Katharina Luther Page 6

Katharina Luther Read online

Page 6

Dear Kathe,

I hid this letter in the shoe for fear of censors at your gate. I’m sure you will have had the sense to find it. Of course it all depends on Sebastian getting there and not being robbed on the way. The roads are so dangerous, we’re warned not to travel after dark. But it’s not always possible to reach a safe billet before nightfall when the days are so short so I am praying for him. I have a sort of feeling Sebastian is leaving home, though he did not say as much. Father and Stepmother will miss him, he’s been such a help to them since old Blankenagel took to drink and poor Magde is getting old and worn out.

But I don’t really blame him. The peasants are fed up. Pay is so low now, and rents high. They hear the older people complaining about how much better it used to be. They want to work for decent money, to learn a trade, to have a home of their own. They don’t want to pull their forelocks to the Squire and all his family, with the constant threat of eviction from their cottages.

Christian says it’s a recipe for civil war, the peasant classes becoming so unruly and disrespectful. I’m glad we live in a town – our servants are well paid and well fed, so I don’t think there’s any danger of them leaving or becoming unpleasant.

But that’s not the half of it. All this trouble with the church, you wouldn’t believe the commotion! It’s largely because of a man called Dr Luther in Wittenberg. I’m sure you will have heard about him. He got into trouble with the papal authorities because he nailed a piece of paper on the church door saying what was wrong with the church. It was a long list of complaints; they were called theses. Anyway, they sent him for trial in Worms, and on his way home he disappeared and everyone thought he must have been murdered; so then of course a lot of people were sad and said what a pity, such a great man, a priest and theologian, cut down in his prime because he dared to speak his mind. But a year later, lo and behold, he popped up again, apparently he’ d been in hiding all that time, and some people forgot how they had been sad at his death and started complaining about him all over again. I’m just telling you this, though you probably know it already, because I have the opportunity of getting a letter to you without (I hope) its being confiscated by your Abbess.

The latest scandal is unbelievable: we heard a fresh eye-witness account from a friend of Christian’s called Heinrich. He’s studying theology at Wittenberg. He stopped with us for a night on his way home to Görlitz for Christmas and he was boiling over with the excitement of it, of what happened there, and this is what he told us:

The church in Rome ordered Dr Luther to stop preaching and lecturing and recant all his previous declarations against the Church such as his Ninety-Five Theses and all the other books and things he had preached and written. All his books containing such material must be burnt. If he did not recant within sixty days he would suffer excommunication and many of his colleagues and accomplices too. That time expired on December 10th. At nine o’clock on Sunday morning, December 10th, he posted a notice on the door of the lecture building in Wittenberg inviting all students to come and witness a burning of the godless papal constitutions and writings. A huge fire was prepared just outside the Elster Gate behind the hospital. A great throng of students gathered there and the master kindled the heap of wood. Then Dr Martin Luther threw the anti-Christian decretals, together with the recent bull of Leo X, into the fire. He said as he threw them onto the fire: “Because you have grieved the saints of the Lord, may eternal fire grieve you.” Then the doctor walked back to the city, followed by a great many doctors, masters and students. But that was only the beginning of a whole day of burning and riotous behaviour. Bonfires were lit all over the town, in the school yard, on a farmer’s wagon, on street corners. The crowds sang bawdy songs and played trumpets and waved papal bulls about; some men stood up on wagons and read them out in silly voices and everyone laughed in scorn, then they were shredded with swords and flung on the fires with ribald singing and cheering, along with heaps of other papist books and pamphlets and decrees. It seemed unthinkable that people should dare to treat papal documents with such disrespect.

The next day Dr Luther stood up on a dais in the town square and declaimed in his booming voice, so that it echoed about the houses: “These bonfires are nothing but child’s play. We should not stop at burning the writings of Rome, we should burn the Pope himself, that is, the Roman papacy, together with his teaching and cruelty. Unless you contradict with your whole heart the ridiculous rule of the Pope, you shall not be saved. For the kingdom of the Pope is so contrary to the kingdom of Christ and to Christian life that it would be better and safer to live all alone in a desert than to live in the kingdom of the Antichrist.” What happened in Wittenberg on December 10th, and the following days, has caused an uproar all over the country, it’s almost as if a fire is spreading, a fire of dissent, all over Germany. As you can imagine, Father and Mother were horrified when I told them this story, they said everything is going to rack and ruin.

In telling you this I am taking a risk. But I feel sure you would want to know, if you have not heard about it already.

Dear Sister, be careful and stay where you are, Christian feels it is the safest place for nuns, to stay behind walls in these turbulent times.

With all our love and best wishes,

I sat very still after reading this. Some people say it won’t be long before the end of the world. Apocalypse. The signs are there, the portents. But how will the world end? Will it be consumed by flames or be inundated beneath another flood? Or maybe it will become very cold and freeze and be covered with ice so that all creatures die. Which would be preferable? Drowning, freezing or burning? On the whole, I could most easily imagine the world being consumed by flames, in raging fires, spreading uncontrollably, the wrath of God at us, poor sinners. Dante’s Inferno.

I thought of all the bonfires I had enjoyed as a child. Fires on Easter Saturday, the return of light; on that day, every single fire in the village would be extinguished. Then, on Easter morning every family, every household, would go with a taper to fetch a flame from the fire in front of the church and take it home to rekindle their own home fires. It meant that we all burnt the same fire from the same source, to symbolise a sense of unity. We used to light fires on Walpurgisnacht, the night before May Day, for scaring away witches; we felt joyful at the coming summer but afraid too, of pestilence and hunger. Then there were the Midsummer fires, when everybody marched round the fields carrying torches, and bones were flung on the fire to drive away dragons; when boys would set a wheel alight and roll it down a hill. In November we had the bone fires after slaughter. These festivals were part of our childhood, and in a more muted way we celebrated them here in the convent. They were fires of celebration, cheerful occasions of laughter and conviviality.

This was different. We now heard about horrible fires where the Church was burning books as seditious, where people were burnt for heresy or witchcraft. And now this: fires of defiance, the burning of papal decrees, the people up in arms defying the Church! My feelings were confused. On one hand I was scared, shocked, appalled. But also, in a sort of way I felt excited and wanted to be out there too, sharing in this restlessness and commotion!

Chapter 6

Ascension Day

Wenn Gott wollte, dass wir traurig wären, würde er uns nicht Sonne, Mond und die Früchte der Erde schenken.

If God wanted us to be sad, he would not give us the sun, the moon and the fruits of the earth.

A particular event pushed me to that point where I knew I had to leave. It was Ascension Day, 1522. I had been a professed nun for six and a half years. We were setting off, as was tradition for Ascension Day, on a boat trip upstream to a beautiful water meadow known as Bernard’s Island; it isn’t really an island, more of a peninsula, because the river curves round it in an oxbow. Crack willows and huge elms grow on the banks, trailing their leaves to touch the surface of the water; the meadow itself is full of flowers; we fish and paddle and play catch the bean bag, and generally re

lax. Ascension Day was just one of several holy days when we had a complete break from silence and routine, and were allowed to enjoy some sort of trip or day of amusement to lighten our spirits.

But this Ascension Day was different: the skipper had cast off and the brown sails were filling in the breeze, the old black barge horse plodding along the tow path, when we heard a sudden splash at the stern followed by the screams of women. We hurried aft to see what the commotion was and there, in the river, lay a nun, face down, her white habit billowing around her, her black veil spread out on the like bats’ wings on the water’s surface. Sister Clara jumped in after her; (she knows how to swim, as I do) followed by the skipper’s mate; they turned her on her back, lifting her face out of the water, and swam with her to the bank, dragging her up onto the grass. The skipper hauled down the sail allowing the boat to float on the current, back to the jetty. It was Sister Ruth, one of the older nuns; she had tried to take her own life, but had survived. A cart was brought down to carry her back to the sanatorium.

This incident shook us up. I had worked with Sister Ruth in the dairy, but did not know her well; she had seemed to be content and devout. Suicide, even the attempt at it, is a mortal sin, they say your soul goes straight to hell. We spent the rest of the day sitting on the river bank, plucking at the grass and whispering about Ruth, wondering why she had fallen into such despair. Our picnic of cold roast duck and wild garlic stuck in my throat.

That same Thursday evening after Compline I sought out my aunt Lena, as I do in times of crisis. We strolled up and down the orchard as dusk fell, beneath rows of cherry trees in blossom, and she told me Sister Ruth’s story.

“I knew she was suffering from melancholia; I prescribed white poppy and valerian to allay the symptoms. I thought she was getting better. I am very fond of Sister Ruth. When I first arrived here she was my novice mistress. She was a lively, funny woman in those days; she made us laugh. If we were to come close to Jesus, to Our Lady and to God the Father, she told us, we must be able to love one another, and love life itself. We young novices were sitting with her by the river, just there where she jumped off the boat. It may have even been Ascension Day. She said to us: ‘Look at the river, girls. See, it has pools, they’re dark and cool, and that’s where the big fish swim. But there are shallows too, gravel beds and riffles, where the small fish are safe from big ones, marshy stretches with reeds and rushes where dragonflies and mayflies breed, and where bitterns and reed warblers nest. Beavers build their dams too, which alter a river’s course. If a river were nothing but one deep channel it would be boring wouldn’t it? Contrast is necessary for diversity.

‘In the same way, in our devotional life, we need the riffles and gravel beds of fun and laughter: they provide a place in our hearts for inspiration and devotion. Let those little fish swim in the shallows of recreation and they will grow into bigger fish in the deep pools of prayer.’ She spoke to us like that, in images which were fun to listen to and easy to remember. We all loved and admired her. But recently she has become withdrawn, and we assumed she was suffering from rheumatism and toothache as so many of the older nuns do. But I was unaware of the extent of her wanhope.”

“What’s wanhope?”

“It’s when your hope fades away, it’s like despair.”

“Have you ever had it, aunt?”

“Yes I have, but only now and then, usually in February when the days are short and cold. When the days get longer I feel better. Anyway, we gave her a hot bath and put her to bed in the sanatorium, and she ate some chicken soup. I sat by her bed for a while, and she told me what was wrong. For the last three visitations of the Bishop she confessed to him that her heart was no longer in her prayers, that she was bored during the offices and unable to pray deeply. The only thing that lifted her spirits now, she told him, was working in the dairy. The cows seem to soothe her, she says. The Bishop was displeased, and on the third such confession he grew impatient and said:

‘Sister Ruth, if you cannot rise above your accidie you will forego the privilege of burial in hallowed ground. I shall have no alternative but to have you buried, when your time comes, in a field outside the convent walls.’

“So Ruth thought, ‘then I’ll make sure I die in the river and go to a watery grave among fish; I’ll be washed down to sea and rest with mermaids. The Bishop wants me to rot in unhallowed ground like a dog trampled beneath grazing cattle.”

“I thought she liked cows.”

“Don’t be facetious, Kathe. It’s the unhallowed ground, the insult, the torment in Hell she is afraid of.”

“I think that was very cruel of the Bishop.”

“So do I, Kathe, in confidence, and the Abbess was furious when he told her. But the fact is that accidie is a sin and must be punished.

“Supposing you just can’t help feeling miserable; how can you dispel doubt if it creeps in? Jesus forgave Thomas, didn’t he?”

“He did. And sometimes I feel the rules are a bit too rigid, but on the other hand if things are allowed to become lax, there lies perdition.”

“Tante – I mean, Sister Magdalena…”

“Yes, Sister Katharina?”

“Can I ask you something, very confidentially?”

“You may, but I can’t promise to be able to give you an answer.”

“You won’t tell on me?”

“I won’t tell on you.”

I peered about us to make sure no one was listening, as we strolled slowly up towards the abbey, our habits swishing through the dewy grass. It was almost dark and crickets were rasping and bats were swooping among the trees above our heads. I heard their high piping cry which older people cannot hear.

“Do you ever want to escape from here? I mean, to go out into the world and not be a nun?”

“No, I don’t. I am content here. I’d be terrified if I had to leave, I know nothing about the secular world. No, I’ll stay here until I die, among other sisters, in the routine of the Rule. But you, dear girl, you’re feeling restless, I can tell.”

“Yes I am restless. I feel left behind. So much is happening outside. Things are changing. It’s happening out there! Bonfires of books, defiance of Rome, of even the Pope himself. We’re stuck here, left out of all the excitement; we whisper about it at night, in the dormitory. We want to leave, Tante. The thought of growing old here is driving us mad! Aren’t we allowed to change our minds, and leave?”

“You’ve taken solemn vows, Kathe. Unless your parents asked for your release, it’s well nigh impossible. And what would you do in the outside world, how would you survive without a male sponsor? It’s a dangerous and mean world out there!”

“But don’t you see, we want danger, we want excitement, we want to be part of the new way of worshipping; children are being taught to read, so everyone can understand the Bible in German. We can work as teachers, we could teach older women to read. But it’s not just that. The peasants here, they have such fun, they’re full of life! They laugh and dance and tease each other. And another thing: we never meet any men! I want to marry, Tante Lena, I want to know what it feels like to be loved by a man; I want to have babies, to hold a baby to my breast as Mary did Jesus, to give suck. And wouldn’t we be more useful out in the world, with all the troubles and upheavals, and angry peasants roving about; we could do more outside than we ever could here, shut up within these walls. But please don’t tell anyone!”

“Of course I won’t Kathe! You’re my brother’s child, how could I betray you? Am I right in thinking that a certain Doctor of Divinity is behind these seditious thoughts?” We had come to a stone bench set into a yew hedge, and sat down together. The stone was still warm from the sun though the air was cool; a full moon was rising behind the tall elm and stars were beginning to appear.

My aunt was right. Dr Luther’s writings had unsettled us, made us hanker for more. For some reason, though, I was unwilling to admit that it was he who had made us question our future as nuns. But in my pocket I had a well-

worn sheet of paper. I had carried it round, and referred to it, for so long that it had grown polished and soft, like cloth. On it I had copied out in my best hand extracts from Dr Luther’s writings: essays, sermons and pamphlets which had been smuggled into the convent; we nuns fell on them as hungrily as pigs at the trough in the morning; we read them, and copied down from them in secret, then passed them on one to another, furtively; we passed them while kneeling in the choir stalls at Prime or sitting on the bench stitching in the tapestry room, or bent over a tall desk in the library copying manuscripts. Hot printed material, exposure of injustice, out-dated restrictions, sclerotic laws, the dead hand of the Church in Rome. We passed them on while out weeding in the walled garden, or after washing out the stilling pans and pails in the dairy. I drew the paper from my pocket and peered at it, realising that it was now too dark for me to read. Never mind, I knew most of the quotes by heart.

“Tante, I don’t know whether you’ve read much of Dr Luther’s work, but can I quote you some of the things he has written – things which have made us question what we’re doing here?

“Please do, Kathe.”

“Priests, monks, and nuns are duty-bound to forsake their vows whenever they find that God’s ordinance to produce seed and to multiply is powerful and strong within them. The church has no power by any authority, law, command, or vow to hinder this which God has created within them.”

“And you do you feel this ordinance strongly?”

“We all do. And this one’s from an open letter he wrote this year: ‘A woman is not created to be a virgin, but to bear children. In Genesis 1 God was not speaking just to Adam, but also to Eve when he said ‘be fruitful and multiply’ as the female sex organs of a woman’s body, which God has created for this reason, prove. God establishes chastity not through our oaths or our free will but through His own powerful means and will. Whenever He has not done this, a woman should remain a woman and bear children, for God has created her for that; she should not make herself to be better than God has made her.’”

Katharina Luther

Katharina Luther